KPIs are used extensively in all types of organisations. There are many KPI approaches, but only one method to develop and use KPIs.

Let’s investigate how KPIs developed, how they are used and the various KPI approaches. As we do this we will see the short comings of popular KPI approaches and discover the performance measurement method that works.

Maybe it’s just me, but does it seem to you that the way KPIs are used appears sometimes to be like a game?

I often hear people refer to their ‘tick-a-box KPIs’ that appears to be a game they complete (and yes some compete) for the ‘managers’.

This idea that KPIs are a game is real. People compete – using poorly formed KPIs – to reach their quotas of all sorts of things. These KPIs often also come with consequences, such as, rewards and punishments.

The use of KPIs as part of the game of reward, recognition and disengagement for many, started back in the 1970’s and is still prevalent today.

KPIs and The Game of Work

Charles ‘Chuck’ Coonradt formed his business in 1973 and then released his book (The Game of Work) in 1984. He has released three books since that one. Chuck had observed that (most) people considered their work a ‘drudgery’ and many of these people were the first to leave right at 5pm. However, these same people invested lots of effort (and money) into their hobbies and sports.

Therefore, to answer the challenge at the time that, ‘productivity in the U.S.A. was not up to world standard’, Chuck decided to gamify work to make it more rewarding for employees and the business. This manifested in KPIs becoming daily/weekly targets, points systems, and the use of leaderboards.

Chuck is still active today. The claim on his website is that he has engaged with over 1 million business leaders about Game of Work and taught companies such as, Coca-Cola, Microsoft, AT&T, Time Warner, Boeing, and Wendy’s.

Using KPIs as part of the gamification of our work, to me seems as if we are trivialising our work. There is a strong argument against competition in teams (that creates winners and losers), notably by Alfie Kohn in No Contest.

However, there is no doubt that Chuck Coonradt’s ideas about using KPIs as part of the game of work are still around today.

Whilst KPIs may be used this way, it is not a KPI approach that is useful.

Here is a Forbes article on Chuck and the Game of Work.

Also have a look at: Let’s Ban KPIs.

The Balanced Scorecard

Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton introduced us to the Balanced Scorecard through an article in the Havard Business Review (1992) and the book of the same name in 1996.

The Balanced Scorecard helped us move away from only measuring the financial elements. KPIs typically linked to income or expenditure. The numbers that impact the two sides of the balance sheet.

I was involved in a Balanced Scorecard implementation in the late 1990’s in a large financial services group, and we struggled. We got the strategy side of the Balanced Scorecard – that is moving away from financial and activity KPIs linked to budgetary numbers – to a broader set of performance measures.

However, finding KPIs for each of the quadrants of the Balanced Scorecard was difficult. Why? Because we had no method or technique to develop our performance measures. We only had the ad hoc approach to KPIs we had been using previously. We still got our balanced scorecard together though, we just had some, meaningless KPIs in each of the quadrants. Job done. Project complete.

Balanced Scorecard is not a KPI methodology. It was a useful step forward in our thinking about measurement beyond the balance sheet. Needing performance measures to understand how well we are performing across the broader elements of the organisation (customer, learning and growth (culture), internal systems and processes) was a paradigm shift we needed at the time.

Here is a link to the HBR article of 1992.

Whilst global practice in performance measurement benefited from the Balanced Scorecard, we have moved on, since the 1990’s. Yet, there are many managers and leaders that still use the scorecard. Why? Maybe because it seems to be a convenient of way of listing KPIs into four quadrants. Perhaps that’s a simple way to structure bonuses. Maybe it is also because many Board members are familiar with the Balanced Scorecard.

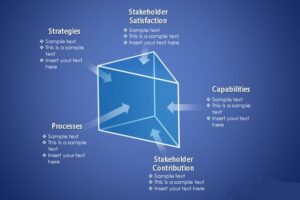

The Performance Prism

This approach to KPIs developed from the limitations of the Balanced Scorecard. Neely, Adams, and Kennerley released their thinking in their book of 2002, The Performance Prism.

It was born out of the restrictions of the four quadrants in the scorecard.

Therefore, Neely et al, contended that organisations and businesses had many competing stakeholders whose needs also needed to be considered when developing KPIs. Additionally, they identified that often changes had to be made to the ‘strategies, processes and capabilities’ to meet the competing needs of the broad group of stakeholders. They also identified the fallacy that, ‘if you measure the right things, the rest will fall into place’. Which is more often not the case with KPIs.

They also suggested that the various stakeholder groups required something in return from the organisation, and those expected returns should also be measured. For example, employees are a stakeholder group that also expect something. Perhaps, to be safe at work, to be treated fairly, to be given meaningful work to do that makes a difference in the lives of their customers.

However, the Performance Prism does not provide a way to design, select and use meaningful performance measures.

The Performance Prism

Likewise, The Performance Prism is not a KPI methodology. It was another useful step forward in our thinking about measurement beyond the finance realm.

Here is an article on ACCA Global with more about the Performance Prism.

OKRs – Objectives and Key Results

We were first introduced to the idea of Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) in Measure What Matters, by John Doerr (2017). Wikipedia states Doerr: ranked as the 40th richest person in tech in 2017 and, as of 1 August, 2023, as the 146th richest person in the world, with a net worth of US$11.9 billion. I suggest it was his profile that made this book successful and sparked a flurry of activity called OKRs. But the book definitively does NOT instruct you on how to measure what matters.

This book perpetuates the old fallacy mentioned earlier: ‘if you measure the right things, the rest will fall into place’. Surely, we need a method to figure out what the ‘right’ outcomes are and then a technique to select the ‘right’ measures. Not covered by John Doerr.

Instead, Measure What Matters (2017) provides anecdotal stories of various leaders and mangers that have found success. Through these stories, various examples of OKRs are used, but there is no formula for how to write an OKR. Each leader-story does it differently. From the information provided for these OKRs and attached KPIs, there is nothing you can learn about how to do it.

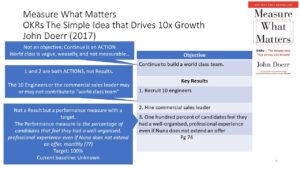

OKR Example 1

For example. Page 74 of the book. As you can see the “objective” is a pretty vague action to continue something. Likewise, the “key results” listed are also actions (rather than a result or an outcome). These actions could be completed but no progress towards the “objective” could be evidenced by completing the action. Resulting in unclear language.

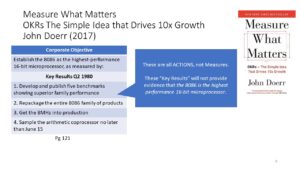

OKR Example 2

Or this example on page 121. Appear to be actions, not performance measures or KPIs.

The “Typical OKR Cycle” that Doerr presents on page 267 starts with, “Brainstorm Annual and Q1 OKRs for the Company”. “Senior leaders start brainstorming top-line company OKRs”. Now, brainstorming is a great technique for generating ideas. But I would have thought that leaders were far better off having some evidence of the current level of performance before they start brainstorming ideas for OKRs. Whilst some of these OKRs will use some target orientated language (achieve 75% (the target) of something (the measure) by June 30 (the milestone); setting targets without knowing the current level of performance is often the recipe for unachievable targets, or encouraging people the manipulate or game the measure to achieve the target.

There are some better examples of OKRs on the ‘what matters’ website, but there is still no method for how we do this. With no method it means OKRs cannot be consistently used the people and teams to write meaningful goals, or objectives. And with no method it also means the organisation cannot build capability in OKRs.

To me OKRs seem like a modern day example of SMART goals, but without any research behind it.

PuMP® the Performance Measurement Process

PuMP®, developed by Australian statistician Stacey Barr is the only comprehensive KPI methodology available today. Based on my work and research I have done over the last 20+ years. PuMP® was produced from many years of research, and is around 20 years mature.

PuMP® is used around the world by organisations seeking to:

- Build capability in how to measure performance and create meaningful KPIs

- Create a consistent language about what measurement

- Have a consistent set of tools and techniques about ‘how to’ do performance measurement

- Use a method that takes us from our purpose with measurement, through the development of a measurement framework and using performance measurement to improve performance.

In other words, PuMP® was born out of the struggles we all have with the various approaches to KPIs.

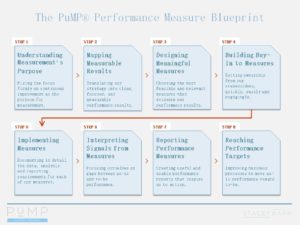

The Eight Steps of PuMP (the Performance Measurement Process)

You can read more on the PuMP® method in:

- The Eight Steps to a High Performing Organisation (and meaningful KPIs)

- Why we use Methods – a dive into what methods are and the benefits of using methods

My KPI Journey

Early in my professional career I was a manager in a financial services business, lots of KPIs. For many years managing teams with KPIs and targets. Also, more than three years managing a large contact centre. We had KPIs and data everywhere. But meaningful information about a broad range of aspects of our performance was missing. We became competent at creating stories from cobbled together pieces of data that told the story we wanted to tell. Through trial and (a lot) of error over a few years of finetuning quarterly KPIs we landed on meaningful measures of performance, for the business and individuals. If we had the method for performance measurement (PuMP®) then, we would have achieved this in one quarter.

Completing an MBA with the Graduate School of Business (QUT, Brisbane) only reinforced these, old ad hoc KPI approaches. The text books were generic saying we need to set KPIs on key roles and activity we saw as important. But no way about how to do this. No formula about how to even write a KPI.

Two years into my consulting career, I learned the PuMP® (Performance Measurement Process) from Stacey Barr. I could not go back to my old KPI ways. I have used and advocated for PuMP ever since.

This article has attempted to a look at the various KPI approaches available and see the difference between an idea about KPIs and a method for developing a meaningful measurement framework.

Summing Up KPI Approaches

There are many, many approaches to KPIs. The common or popular approaches are covered in this article. But there are so many other approaches that various leader/managers have cobbled together that means almost every organisation takes a slightly different approach to KPIs.

Currently (2024) there is only one method for performance measurement (KPIs) in the world, and that is PuMP®.

So, what is a KPI really? Our key performance indicators should be the ‘key’ performance measures we are focused on. There are typically two types of KPIs.

The final word must be that it is far better to use a method to develop and use your KPIs. Just as you do for so many other approaches you use in the workplace.

Learn More About PuMP

For more about KPIs and PuMP visit my page where you can download white papers for more ‘how to’ information.